The coronavirus pandemic continues to negatively affect occupancy in senior living, with percentages released Thursday by the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care’s NIC MAP Data Service representing all-time lows for the sector.

Occupancy at U.S. senior living communities — including independent living and assisted living communities — was 80.7% for the fourth quarter of 2020, the lowest it has been since NIC began keeping records in 2006, NIC Chief Economist Beth Burnham Mace told McKnight’s Senior Living.

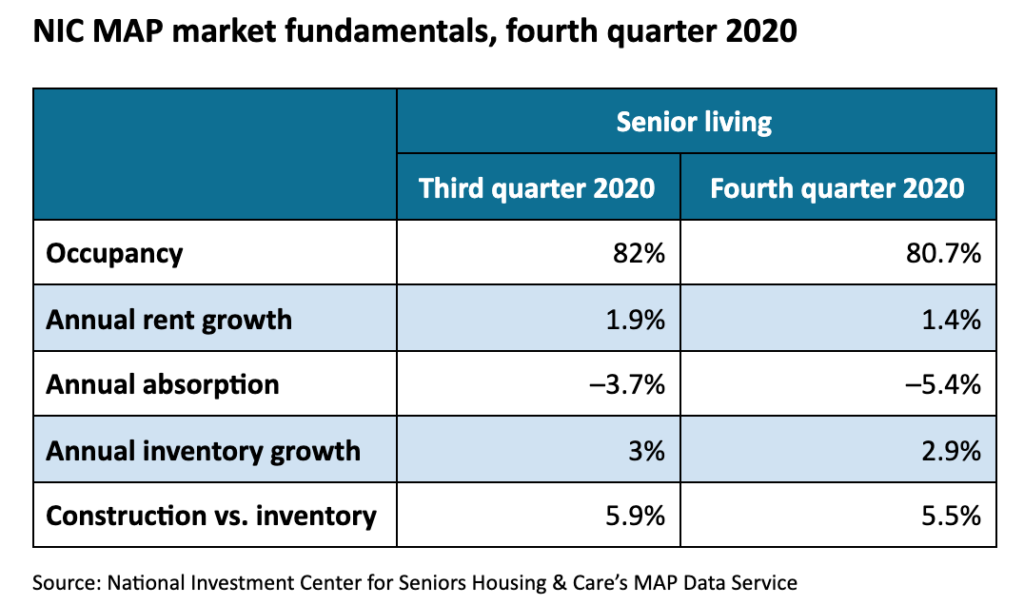

The percentage is a 1.3 percentage point drop from the third quarter, when occupancy was 82%. Cumulatively in the second, third and fourth quarters, occupancy fell 6.8 percentage points.

The good news is that, although “still quite large from a historic perspective,” senior housing occupancy declines were less pronounced in the fourth quarter than in the previous two quarters, Mace said.

But individually, independent living and assisted living (including memory care) occupancy also reached record lows, she said.

Assisted living occupancy fell 1.3 percentage points to 77.7% in the fourth quarter, and independent living occupancy dropped 1.4 percentage points to 83.5 %. Since March, assisted living and independent living occupancy has fallen by 7.4 and 6.2 percentage points, respectively, according to the NIC MAP data.

The drop was greater for assisted living, which typically attracts residents who tend to be more frail and need more assistance with activities of daily living, Mace noted. And yet because assisted living is more needs-based, there is more pent-up demand for such units, she added.

“We’re over nine months now into the pandemic, and if your family member is taking care of you, it may be more challenging after a length of time,” Mace said, explaining the sector’s appeal. “We’re hearing this from a lot of operators, and the pent-up demand does tend to be more for assisted living.”

As more people are vaccinated against the virus, occupancy should improve, she said, noting that many operators have waiting lists, and some are not addressing them due to the pandemic.

“What’s going on is that we’re having a slowdown in move-ins,” she said. “Some of that is reflecting people’s reluctance to move into a congregate setting right now, and some of that is reflecting that some operators are still imposing their own moratoriums on move-ins until they can be particularly safe, or the process of moving someone in can be a little bit intimidating to families, if you have to quarantine for any length of time.”

In many cases, Mace continued, an operator will perform a COVID-19 test before a resident moves in and then another test at move-in, and the operator may require the resident to quarantine for a period after move-in. “That doesn’t feel really good, so that’s having an impact as well,” she said.

“I think once we get the vaccinations out there and people are more comfortable with the idea of moving in, there might be a quick pickup in demand for some operators,” Mace said. “The need really hasn’t gone away, but there’s a reluctance just because of the broader circumstances related to the pandemic.”

Leading by example and also educating staff members will help increase vaccination acceptance, she said. “We need them to get vaccinated for their safety, obviously, but also to build confidence back up for people wanting to move into and live in congregate settings,” Mace added.

But given the surge in COVID-19 cases following Thanksgiving and Christmas, the industry may experience additional disruption in the near term, she said.

Differences across metros

The new NIC MAP data show large disparities between occupancy rates across metropolitan markets. San Jose, CA (88.5%), San Francisco (86.9%), and Seattle (84.8%), for instance, had the highest occupancy rates of the 31 metropolitan markets that encompass NIC MAP’s primary markets, whereas Houston (73.5%), Cleveland (76.6%), and Miami (76.7%) recorded the lowest occupancy rates.

“Some of that is related to conditions prior to the pandemic,” Mace said. “Houston, for example, had supply issues. There was a lot of competition that was going in the market because there was a lot of development that was going on.” San Jose, by contrast, has limited development, she said.

The difference in markets, Mace said, “is really a function of pro-growth or anti-growth attitudes. It has to do with how easy or not easy it is for entitlement. It has to do with tax rates — a whole host of factors that apply not just to senior housing but to any type of commercial real estate.”

The South, she said, generally is more pro-development than either coast. “So going into the pandemic, the occupancy rate in Houston was already relatively low, and that was a function of those supply and demand conditions going into the pandemic,” Mace said.

Inventory

Inventory growth slowed “sharply” for assisted living in the fourth quarter, according to NIC, with 1,626 units added in the 31 primary markets, the fewest since the third quarter of 2013.

In independent living, however, inventory growth was greater in 2020 than it was in 2019, Mace said, adding that the reported numbers for any given quarter represent projects that began 18 months ago and then were then added to inventory.

“If I look at [construction] starts, which is what’s being actively being started right now or developed right now, those numbers are down pretty significantly,” she said, predicting that in 12 to 18 months, “We’ll start to see more impact of a slowdown in supply going forward, because of the limited amount of starts today, which in turn is a function of bank lending practices on new development.”

By the end of 2021 and into 2022, Mace said, “we should start to see the benefits of pent-up demand and a slowdown in construction activity that’s starting.”